Memories of Alan Chadwick by Allen Kalpin

Allen Kalpin began his work in the Garden Project at Santa Cruz in the early spring of 1971. The garden was then in its prime, positively bursting at the seams with incalcuable abundance, and so work soon began on the new farm project located at the foot of the campus. These were tempestuous days, full of tensions and tirades, because a conspiracy against Alan Chadwick was in full swing, and he wasn't taking it lying down.

The upshot of all this grisly business was that a poorly informed university administrator, relying mistakenly on underhanded misrepresentations, fired Alan and handed his magnificent creation over to an underling. Through the timely intercession of Paul Lee, Alan was then approached by Richard Baker, the new Roshi of the San Francisco Zen Center, with an offer to come and initiate the gardens at the newly-acquired Green Gulch Farm. After some preliminary negotiations, this was accepted, and Allen Kalpin and Peter Jorris accompanied Chadwick north to Muir Beach in Marin County, California.

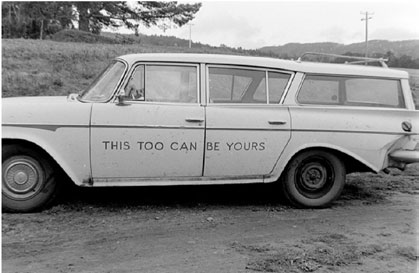

Allen Kalpin here describes the move that the three of them made to Green Gulch and some of the difficulties of that first month or so. The sleek sports car that he refers to at the beginning of his recollection was driven by Richard Baker, himself a very colorful character. Kalpin also mentions another car, the so-called "This Too Can Be Yours," shown below, that Alan Chadwick drove for years. See here for more on this car.

Allen Kalpin, ca. 1969, photo by Greg Haynes

Alan Chadwick's old Rambler station wagon. Photo by E. Gaines. Used by permission courtesy Paul Lee

The Move to Green Gulch

The fast late-model sports car reveled in the curves of that sunny ocean-side road in a very self-assured manner. Of course, it didn’t have a hard act to follow because the usual conveyances were This-Too-Can-Be-Yours jalopies and well worn pick-up trucks. And it made easy work and good sport of the impossibly angled streets of San Francisco where the sparkle of sunshine on waves had given way to drifting wraiths of time-bending fog.

We sat in the minimalist elegance of Baker Roshi’s San Francisco flat. The Zen-inspired interior seemed to harmonize well with the timeless world outdoors. Tea was served. Tea—that soothing common denominator that can gently insinuate a rapport between apples-and-oranges cultures and perspectives—at least for the moment.

Richard Baker had recently taken over as Roshi of the San Francisco Zen Center. He had big sandals to fill. Suzuki Roshi had long been a beloved and respected leader. However, it soon became clear that, despite the initial pause given by the very un-Japanese name, there were reasons why Richard Baker had been chosen.

* * *

After Highway 1 struts north across the Golden Gate Bridge, it turns resolutely toward the sea. Resolute, but not adverse to a bit of meandering, it skirts sacred Mount Tamalpais and drifts on past madrone, eucalyptus, and redwood. But out of respect, it changes course before reaching the coast and heads north, paralleling the Marin County coastline. For between the bend in the road and the perfection of Muir Beach, is Green Gulch. Green Gulch is a sort of land that time forgot, a Shangri-La. In moments of sunshine and clarity, from the tops of the bordering ridges, the white towers of downtown San Francisco can be seen sparkling. But the drifting fog soon envelopes the valley with quiet and obscurity, and it could be a thousand miles from nowhere.

The Nature Conservancy was working to preserve the land, which had most recently been used as a horse farm. Now, under Roshi Baker’s leadership, the San Francisco Zen Center was in negotiations to acquire it. It was to become Green Gulch Zen Center.

* * *

Fifty miles to the south of San Francisco, the broad sweep of Monterrey Bay shines in the distance, far beneath the undulating grassy hills above Santa Cruz. Turn around and you are faced with the dark green forest world where too-tall-to-be-real redwoods stretch on up into the coastal mountains. Sometime in the 60’s, in the midst of the organic farming and back to the land impulse that was germinating in California and spreading across the country, the University of California at Santa Cruz had decided to participate. Led by a small group of visionary professors, the campus agreed to allow a few acres of its hilly land to be used to create an organic garden, to be called the Student Garden Project. This small group of professors also decided that in order to bring this project about they would need a leader and a gardener with experience and vision of his own. They wished for such a person. However, when the world of the academy starts inviting in the forces of nature, there is reason to be careful about what is wished for.

Alan Chadwick had just about single-handedly carved the garden out of the clay soil and poison oak infested hillside. There was a thriving apprenticeship program, and work had started on the new 20 acre farm project farther down the hill. Despite his prodigious accomplishments and deep knowledge, despite his ability to lead, inspire, and change lives, Alan Chadwick did not fit in well with the world of academia. His intolerance of modern agricultural practices, and indeed, of modernity itself, along with his uncompromising advocacy for the world of living things, had created many enemies on campus.

Right around the time that Alan was asked to leave the UCSC gardens, in stepped Richard Baker. Would Alan, and any of his apprentices who might be interested, care to help the San Francisco Zen Center create the gardens at Green Gulch? The vision included a rural retreat center with extensive organic gardens that would both supply Green Gulch and provide vegetables to be sold by the Zen Center in San Francisco.

Over tea in Richard Baker’s San Francisco apartment, there was talk of a melding of visions, a meeting of paradigms. West meets east: a creative encounter between the world of classical European garden design and horticulture with that of an Oriental aesthetic and meditative simplicity. This was heady stuff, especially in the world of turn-of-the-70’s California, which was exploring every variation of west meets east.

* * *

The reality, however, was the bone-jarring slam of a pick-axe into horse-compacted unyielding clay soil. Some months the fog might move out. But not this month. Unrelenting and unchanging, it is the illustration one ought to see when one looks up the word “depression” in the dictionary. Peter Jorris and I were the apprentices who accompanied Alan to Green Gulch. We were holed up in a little trailer, or “caravan,” as Alan grandiloquently called it. Given the fact that we didn’t believe in using machines to till the soil, we were faced with cultivating acres of pasture land with pick-axes. And sunup to sundown, that is what we did.

During that period, Alan was often either ill or away, so the work fell to Peter and I. The arrangement was supposed to have been that the Zen students who were living on the land would participate in the work. However, it ended up that there was a short period every day that they set aside for garden work, with the rest of their hours scheduled for meditation and various other activities.

In the midst of the fog and the sickness and the bad vibes between gardeners and Zen students, Alan and I had some sort of argument. The subject of the dispute is long forgotten, and it was just one of many such arguments that often escalated to shouting matches. However, on this occasion when Alan told me something to the effect that if I didn’t like it I could leave, this time I did just that. I stuck my thumb out on Highway 1 and was soon picked up and was on my way to Santa Cruz. I have been told that very soon after I left, Alan hurried out to the road, but by the time he got there, I had already gotten a ride.

Green Gulch is now a successful Zen center and is home to thriving and extensive gardens. There are simple markers on a hillside where Alan Chadwick is buried near Alan Watts. East did meet west. However, like all such encounters, it was not easy, and the details are still being worked out.

Return to the top of this page